Interview in The Telegraph

How do you read your son a bedtime story when cancer has left holes in your brain?

Martino Sclavi Obituary

Interview in The Guardian

Ghost writer: how Martino Sclavi’s brain tumour helped him write a book

In memoriam

In memoriam

‘Starting to lose… something’

The Daily Telegraph, Saturday 8, July 2017

Chris Harvey enjoys a film producer’s surprising memoir about waking up without a finch-sized chunk of brain.

Six years ago, Martino Sclavi, a 38-year-old Italian film producer, was in Los Angeles working on a new movie about a con-man posing as a priest. His friend Russell Brand was to play the lead, and the finished script was almost due. During a read- through, Sclavi found that he couldn’t quite follow the text. He’d had a headache since breakfast, and felt that his eyes weren’t working well. Later, the headache got so bad that he called an old college friend to drive him to a doctor. He didn’t have health insurance and so was turned away from a number of clinics before the friend rang his own father and explained that Sclavi “no longer seems to be able to answer, or maybe even hear, my questions”. His dad told him to take Sclavi to the ER at Kaiser Permanente Hospital on Sunset Boulevard right away.

The next day, Sclavi awoke to find that a surgeon had cut out part of his brain – at a cost of $100,000 (£77,000), which required a down payment from his mother and sister’s credit cards. He had been diagnosed with a glioblastoma – a very aggressive type of cancerous tumour that had reached its most violent stage. Doctors gave him a 98 per cent chance of dying in the next 18 months. Some six months later, in Rome, Sclavi would undergo experimental cancer treatment and further surgery.

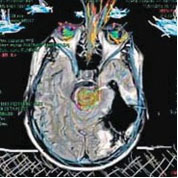

In the most dramatic section of this memoir, Sclavi describes waking up on the operating table, “awake in a way… that I have never been before. It’s not that slow move into awareness. It’s Bang! Reality”. As the scalpel delves deeper into his brain tissue, he is asked to count forwards and backward to 10, and to recite the alphabet. Sclavi is aware that it “really, really hurts” and he is conscious that “we are starting to lose… something…” When it is over, there is a hole the size and shape of a bird in his brain.

As the film-maker begins his slow, odds-defying recovery, he finds that he can no longer read. Over time, he realises the ability is not coming back. Back in the US with his wife, Margarita, and young son, Miro, he goes off on walks, deliberately getting lost so that he can try to read the signs and find his way back. When he is forced to ask passers-by for directions, they often show him maps on their phones, which he can’t read either.

He does find, however, that he can still touch-type and embarks upon the long process of documenting his experiences before and after the events of January 2011. He uses a voice app – which he names Alex – to read back each sentence to him, then he corrects it, and has it read back to him again. This painstaking process heals most of the faults in his typing but not all – he still has to “find a way of telling my son about Daddy’s trip to the moon”.

Sadly, The Finch in My Brain also documents the breakdown of Sclavi’s marriage to Margarita, a psychiatrist from Macedonia. They married in 2004, and his description of their first meeting, the innocence of his love for her, and their gradual coming together, is the most diverting section of his memoir, given depth and colour by being played out against the medieval backdrop of Siena, among his wealthy, idiosyncratic Italian relations.

Margarita adds footnotes to some of the milestones in Sclavi’s painful pilgrimage: “I needed very much to talk to you… but there was only silence… you explained you were trying to make peace with Death, and had no need for help.”

To the reader, though, their separation is inevitable from the moment he wakes up after the second

operation and can no longer recall her name.

Brand also figures large: pre-illness, as an erratic, inspirational figure, fighting his own demons, especially his addiction to drugs and “beautiful, big-breasted girls”; post-surgery, as a loving, supportive friend. Brand lent the house in LA he shared with then-wife Katy Perry to Sclavi and his family during his initial recuperation; he also wrote the foreword to this book in which he describes how his friend went from being “an encyclopedia of opinions on communism, sculpture, movies, Cuba, opera, the whole damn shebang, to a gentle, mindful Shaman quietly watching with a light beyond words in his eyes”.

That’s the other story here: how Sclavi comes to terms spiritually with his altered state and its depressing contours. It’s an uneven book, but it represents some kind of miracle just by its ever having been written, and Sclavi’s optimism shines through it. “As long as the finch in my brain remains happy and doesn’t transform into a dragon or an alien,” he writes, “I feel pretty safe and can have a cup of tea with my sweet, dark-haired friend Death, who is ready to accompany any one of us, at any time.”

The shape of things: a scan of Martino Sclavi’s brain, after a surgeon had cut out his tumour